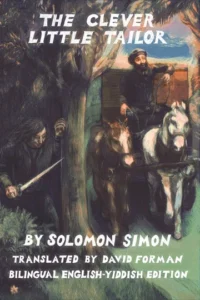

I’m so excited to share THE CLEVER LITTLE TAILOR (Kinder-Loshn Publications, 2021) by Solomon Simon, translated by David Forman with illustrations by Yehuda Blum. This unique translation of a Yiddish tale is about a poor tailor who cleverly solves mysteries in his little town. The book features both Yiddish and English text. The “story behind the story” is as compelling as the book. David Forman is the grandson of Solomon Simon. Out of his love for his grandfather and the stories he wrote, David made a promise to learn Yiddish so he could enjoy his grandfather’s original stories. Years later, after learning Yiddish, David translated and published his grandfather’s work. David is keeping his family’s legacy alive and making traditional Yiddish stories accessible to today’s readers.

It is my absolute pleasure to share my interview with David.

Tell me a bit about THE CLEVER LITTLE TAILOR and how you came to translate the text and publish a bilingual version of the story.

How I came to translate: My road to translation was a long one. I grew up in an English speaking home. My mother’s father, Solomon Simon, was a well-known Yiddish writer. When I was young, he would read to me from the English versions of his books, The Wise Men of Helm and The Wandering Beggar. He died when I was ten. I knew many of his books had not been translated and, in my grief, I promised myself that one day I would learn Yiddish so I could read the rest of them. But there were few opportunities for learning where I was, and I grew up and went on to do other things.

When I finally began to make good on my promise, as a beginning Yiddish student in my fifties, I started with his children’s books. I was such a slow reader at first, often looking up nearly every word in the dictionary. I figured I might as well translate as I went. If I was only going to be able to get through a page or two in a day, I might as well have something tangible from all that time spent.

About The Clever Little Tailor: The Clever Little Tailor was the third book that I got to. It was just a delight to read. Full of humor and courage and even a few bits of poetry and song. By then, my Yiddish was getting better, and I began to think of my translation as not just for myself, but worthy of sharing with others. I daydreamed about a side-by-side Yiddish and English book, so others could do what I had been doing: learning the language by reading my grandfather’s stories.

And [how I came to] publish a bilingual version of the story: Right when I was nearly done with my first draft of the book, I got an email from Jordan Kutzik, from the Yiddish cultural organization Yugntruf. He wrote that they were starting a press, in order to publish classic Yiddish children’s literature with English and Yiddish side by side. He wanted to begin with The Clever Little Tailor, and asked whether I knew who had the translation rights. I couldn’t believe it. Actually, I still can’t.

With the growing interest in Yiddish, how do you think traditional Yiddish stories resonate with young readers today? Why are these stories important?

In the introduction to a different book of his, Simon wrote about how folk stories can be both universal and culturally specific at the same time. Stories, like those in The Clever Little Tailor, of giants, of highwaymen and of an undersized hero who wins, not through strength but through cleverness, are universal. In this particular telling of these stories there are also Jewish pride and frank depictions of antisemitism. There are Yiddish proverbs and idioms sprinkled in. I think these stories resonate for the same reasons they always have. Children love heroes they can identify with, whose deeds are larger than life.

The illustrations are very evocative. Did you work directly with the illustrator, Yehuda Blum?

No. For that, the credit goes to my publisher, Jordan Kutzik, who has been as devoted to the project as I have. He worked with Blum. Only in one or two rare instances did I remind them of a detail from the text. For example, when the text said a tree was a birch tree, the illustration showed that. I especially love the decorated initials that begin each chapter, but can take no credit at all.

I did contribute to one visual aspect of the book. I really wanted it to read from right to left– the natural direction for Yiddish text to go. And that way, even when someone reads the book entirely in English, they will feel viscerally that they are reading a Jewish book. Fortunately, Jordan agreed.

What challenges did you face in the translation process?

So much goes into finding a way to make a story natural in English, but faithful to the original: Deciding whether to translate his characters’ names, which meant things in Yiddish, or to leave them; making the rhyming bits rhyme; trying to convey different tones of speech used by a bandit, a lying shopkeeper, or a king; determining what might not make sense to a contemporary English reader and what to do about it. However, because the two texts were going to sit together across a single page spread for learners to use, I often ended up sticking very closely to the literal text. Luckily, that original was written so well.

What do you hope your readers will come away with after reading THE CLEVER LITTLE TAILOR?

I got an incredible gift from a friend last week— a video of her young son reading the book out loud. When Shnayderl, the little tailor, pulled off one of his tricks, a mischievous grin spread across the boy’s face. That’s what I want, first and foremost: Delight.

For a second group of readers, college students or adults who are using the book to learn Yiddish, I want them to feel like they are finally able to use their developing language skills to read real stories, and not just brief vignettes adapted to textbooks.

Do you have any other translation projects in the works?

There’s a moment in the book when our hero requests a peculiar set of items before setting out to do battle. Cookies with rocks in them, some cheese balls, and a bird. “How,” he is asked, “will you use those things to defeat the giants?” “It’s a secret,” he says. Indignantly told he cannot keep secrets from a king, he admits that he himself does not know for sure.

I wanted to answer that my next translation project is a secret, but the truth is I don’t know for sure what I’m going to do next.

I love Yiddish poetry, I am fascinated by the Yiddish speaking Jewish world in New York in the 1950s, and there is still a lot of Solomon Simon’s work worth sharing. Perhaps one of those three subjects will take me on my next adventure.

Thank you, David!

David R. Forman was first a calligrapher and graphic artist, then a psychology researcher and college professor before finally returning to his early love of writing. His poetry has been published online, in anthologies, and in literary journals. He began studying Yiddish in his fifties, in order to fulfill a lifelong vow of reading his grandfather’s work. For the last two years he has worked at Cornell University, teaching Elementary Yiddish and cataloging Yiddish manuscripts in the university’s library. You can learn more at www.davidrforman.com