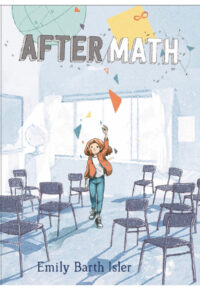

Emily Barth Isler is the author of AFTERMATH (Carolrhoda Books, 2021), a beautiful, honest novel about empathy, compassion, and the deepest kind of loss. In the story, Lucy grapples with her grief over her little brother’s death. But when her family moves to a new town that had experienced a school shooting, Lucy finds solace in an unlikely friendship. AFTERMATH is a multi-layered story that offers readers a serious but necessary insight. Lucy’s story, and the stories of her classmates, will stay with readers.

It’s an honor to welcome Emily and learn more about this important book.

AFTERMATH is a story of love, loss, and trauma. Lucy has lost a brother, and her new classmates have experienced a school shooting. As a writer, how did you balance these different experiences and perspectives?

It was very important to me that the readers’ point of entry for the story was an outsider to the school shooting. Most of the people who read the book will, themselves, be outsiders, and I wanted them to have Lucy as their portal into the fictional world of Queensland, VA. However, as you said, Lucy has also experienced loss, though it is a different loss. One of my goals in writing AfterMath was to inspire the kind of empathy we all should have for every human we encounter. There’s that meme, “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a battle you know nothing about.” (It’s been attributed to at least four or five different people, so I will leave it unattributed). I think this is a wonderful, important way to go through life, and something really valuable for kids to think about. Everyone you meet has a story.

Although AFTERMATH is fiction, your characters and their experiences are realistic. Did you do any kind of research to help you create authentic characters?

I read every article I could find about the ongoing gun violence crisis in America for a few years. Sadly, it felt like a daily occurrence that a new piece of journalism would come out that somehow gave me insight, empathy, and ideas about what life was like for the characters in my book. I have also consulted pediatricians, psychologists, and survivors themselves— really generous people who have shared their experiences with me, and graciously agreed to read the book— to make sure it was a sensitive and as helpful as possible.

Lucy and her family are Jewish. In what ways does their Judaism impact them throughout the novel?

The first and most obvious of ways that we see Judaism impacting Lucy’s family is when her mother, Victoria, talks about her own grandparents who were Holocaust survivors. She makes the connection that they, much like Lucy’s new classmates, witnessed unspeakable horrors and tragedy, and yet still managed to go on and find meaning and joy in life. Sadly, most Jews have learned this lesson via their own relatives or through stories of Jewish persecution and suffering, but it has taught us that there is often another chapter, and hopefully a way to continue on and find that joy and meaning.

Lucy’s forgiveness of Avery, when Avery tells Lucy’s secret, is inspired by Jewish teachings, too. The ideas of second chances, repentance, forgiveness, and trying again are things we learn when we all go to synagogue for Yom Kippur and collectively disclose our mistakes, vowing together to do better in the next year. We ask each other for forgiveness every year on that holiday, which is great practice for doing it in everyday life, as well as a reminder that it is necessary, and means that we’re human.

I also think of the Passover Seder when I think about Lucy and Avery, like the phrase “Let all who are hungry come and eat.” There’s always a space at the table. Technically, in the book, it’s Avery’s table that Lucy sits down at, but in the more practical sense, it’s Lucy who invites Avery to be part of her life.

I think Lucy’s whole friendship with Avery is very Jewish in that she is offering space at the table to someone who has historically been excluded. She welcomes the stranger, even when she, herself, is also a stranger. Even once she learns why Avery is an outcast, Lucy doesn’t let other kids’ actions change her feelings about being Avery’s friend. She sees that she’s in a unique position to offer friendship to someone who is so desperately lonely, and she does. And later, she forgives Avery’s mistakes and gives her a second chance. I can’t think of anything more inherently Jewish than that!

I was certainly inspired by my own Jewish values and things I learned in my Jewish upbringing to write this book, and I think the idea of keeping loved ones alive after they die by remembering them and talking about them is a way that Lucy’s family is influenced by Jewish teachings. I actually named Lucy’s parents, Victoria and Beau, after two people who died before I started working on the book, the same way many of us name our children after relatives we’ve lost in the Jewish tradition. Victoria is for our family friend, Vickie Gelfman, and Beau was named for President Biden’s son, both of whom died of cancer in the year before I began writing AfterMath. I felt compelled to infuse meaning and remembrance into the story whenever I could. (The grandparents Victoria speaks of are named after my husband’s grandparents, to whom I was very close!)

What do you hope young readers come away with after reading AFTERMATH?

I hope that parents and kids alike will see AfterMath as a vehicle through which to have hard conversations. I know that AfterMath is not the answer to gun violence in schools— that situation is far more complex and requires moving bigger mountains than I can with my words. While I hope the book is a step in the right direction, I mostly hope it’s a conversation starter. School shootings are a taboo conversation for a lot of kids. Many don’t know of their existence yet. Others will see about them on the news or hear about them in school. Most kids in the United States participate in Active Shooter Drills of some kind, and even if the school calls them something else, kids will eventually figure out what they’re training for, huddled in closets and hiding under tables.

I wanted to give them a chance to say the scariest things out loud, to read the words they’re too scared to imagine, to put themselves in the shoes of those they never hope to be or understand. I wrote AfterMath because losing someone I love is my greatest fear. Writing into my fears is one way I deal with them. Putting the words out there makes it all a little less scary. It takes some of the power back from the fear and gives it to me, the author.

I want kids who read this book to know they have the same options. Writing about your scariest fears can help take the intensity out of them. Talking about your deepest worries might make them less powerful. Reading a book about something that scares you doesn’t make it any more or less likely to happen, it simply gives you the tools to talk about it with a grown up you trust. It takes away the mystery a little bit.

And for parents who, like I do, sit helplessly by their child’s bed at night, hoping something awful like a school shooting never happens to their kid, I see you. But refusing to talk about it— in an age appropriate manner, of course— doesn’t help anyone. I want this book to give you a frame in which to see, feel, and talk about these fears we all have.

The likelihood that each of us will encounter someone in our life who is directly affected by gun violence grows every single day. Every time a mass shooting happens, every time a child is tragically shot, the survivors of gun violence multiply. And every time one of these horrible events is covered by the news, as they must be, we are all affected.

The truth is, we’re all victims of gun violence in some way. Not to say that we’re all equally affected— surely, those who live through incidents first-hand are not the same as those of us who observe from the outside— but any parent who has ever dropped their kid off at school and feared for their safety, every family who has ever worried on their way to temple or mosque or church that a shooting might occur, every one of us who hears a loud noise and worries it’s a gunshot, is a victim of this epidemic. We are all affected, and we must all deal with our collective trauma. I hope that reading AfterMath is part of that healing for the people who read it. I hope it starts some conversations that need to be had. I hope it makes some kid out there feel less alone.

Thank you, Emily!

Emily Barth Isler is the author of AfterMath, a middle grade novel about grief, resilience, friendship, math, and mime. Activist and comedian Amy Schumer calls the book “a gift to the culture.” Emily lives in Los Angeles, California, with her husband and their two kids. A former child actress, she performed all over the world in theatre, film, and TV. In addition to books, Emily writes about sustainable, eco-friendly beauty and skincare, and has also written web sitcoms, parenting columns, and personal essays. She has a B.A. in Film Studies from Wesleyan University, and really, really loves television. Find her at www.emilybarthisler.com