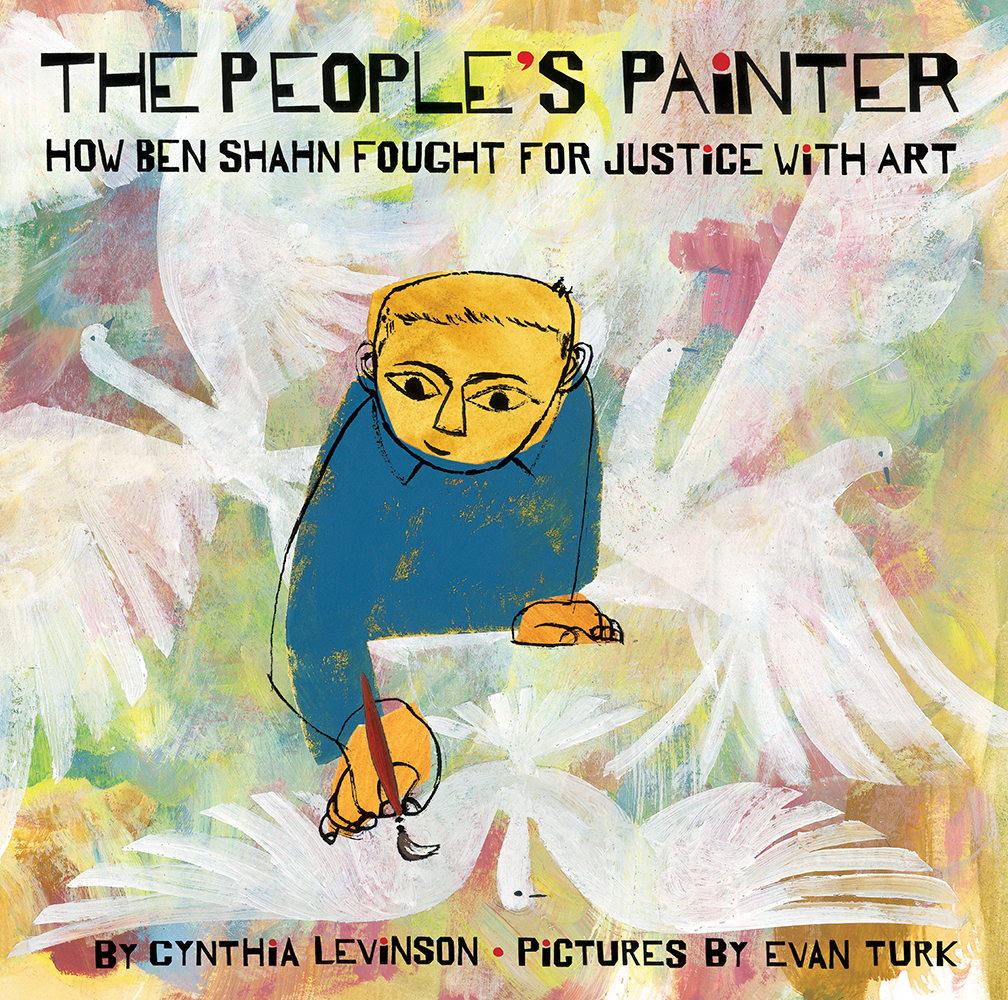

In their new picture book biography, THE PEOPLE’S PAINTER: HOW BEN SHAHN FOUGHT FOR JUSTICE WITH ART (Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2021), author Cynthia Levinson and illustrator Evan Turk introduce young readers to Ben Shahn, a prolific Jewish artist. Social justice was a core theme in Ben Shahn’s life, and his paintings reflected the world around him.

This fantastically illustrated and inspiring story offers unique insights into the life of an important figure in both the Jewish and art communities.

I interviewed Cynthia about her book WATCH OUT FOR FLYING KIDS! in 2015, and I am happy to have the opportunity to chat with her again.

Welcome, Cynthia and Evan!

What inspired you to write about Ben Shahn?

Cynthia: I’ve been aware of Shahn for a long time. As a young person, I knew about his Passover Haggadah. I remember seeing his drawing of Dr. King on Time magazine’s cover in 1965. And Shahn’s peace dove became the iconic symbol of Eugene McCarthy’s anti-war presidential campaign, which I worked on in 1968. Then, I met his second wife, Bernarda, at a high school reunion in 1993, though we attended the school in Columbus, Ohio about four decades apart. However, I wasn’t writing for young readers then. The idea started percolating in 2012 when my first book, We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham’s Children’s March, was published. Since I write about social justice and I’m Jewish—both of which are themes in his work—Ben Shahn seemed to be a natural fit.

What were your thoughts when you first read Cynthia’s manuscript?

Evan: My first thought was “Yes, please let me illustrate a book about Ben Shahn!!” But my second thought, was that even though I have loved his work for a long time, there was a lot that I didn’t know about him. I thought Cynthia had created such a humanizing portrait of him, particularly his childhood in Lithuania and New York, and I thought it was such a beautiful way to frame his life. I loved the idea of kids (and adults) getting to see the winding path and struggle of finding out what kind of artist you want to be, and this book did such a nice job of that.

What challenges did you face in the process of researching Shahn’s life? Are there any interesting anecdotes you’d like to share that didn’t make it in the final version?

Cynthia: There are always challenges when the subject of a biography and his contemporaries are deceased. (Of course, there are other problems when they’re alive!) For me, there is no substitute for “being there.” So, visiting Shahn’s home and studio and viewing his installations were paramount. But they’re all dispersed. He lived and worked in Roosevelt (formerly Jersey Homesteads), New Jersey. The Whitney Museum in New York City holds part of the Sacco & Vanzetti series. Murals are installed in public buildings in Washington, DC and elsewhere. It took three trips to view his murals at the Post Office in The Bronx, which were literally under wraps because of construction! But it was all worthwhile because I talked with his son and neighbors and saw some of his work in situ, the way he intended.

Thank you for asking about anecdotes that fell out of the final version! It was wrenching to leave two stories, in particular, on the cutting-room floor. When Shahn was an apprentice lithographer, he couldn’t figure out how to space the hollows within and between the letters so they looked pleasing. The master showed him how to pour water into the tray of type and adjust the lettering so the volume of water was even throughout. Once he absorbed the lesson, he said, “only the eye and the hand can measure them.” His description is graphic but also arcane, and Evan conveyed the point by highlighting hands and eyes in the illustrations.

The other story relates to Shahn’s helping the Mexican artist Diego Rivera paint a mural at Rockefeller Center while it was under construction. They included a portrait of the Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin. Nelson Rockefeller was so incensed that he had the mural destroyed, after which Shahn led a protest march in New York City.

Tell me about the medium you used for your illustrations? Also, what challenges did you face in reflecting Shan’s style while still making your work uniquely yours?

Evan: For this book, I primarily used gouache (a type of opaque watercolor). I also used a bit of acrylic, linoleum block printing, and pencil, but most of it is in gouache. I thought this medium worked best to approach many of the different mediums Shahn used (like oil, acrylic, watercolor, and gouache) and also would make for vivid colors and sharp crisp lines. A technique I used a lot on this book was to cut masking tape into many tiny strips and then use those thin strips to mask off sections so that I could get those sharp, crisp shapes that Shahn had in his work.

I don’t know how much I consciously thought about having to make the illustrations feel like me, I was more concerned with figuring out what things made his work so captivating. Whenever you’re studying an artist, you’ll never make a 100% accurate copy, and your own personality shines through anyways, so I wasn’t too worried about it looking too much like him. But I really wanted to find little bits of how he distorted figures, or when he used shape, versus pattern, versus line, and how he composed his pictures to give the book the true feeling of his work. His work has so many layers, and I really wanted to bring that through.

What were your thoughts when you first saw Evan’s lovely illustrations?

Cynthia: I was stunned speechless! I shouldn’t have been because I was ecstatic when Evan agreed to illustrate our book. But I didn’t really appreciate how masterful he is until I saw how perfectly his artwork channels Shahn’s styles and passions, how his spreads convey the love within Shahn’s family yet the disorientation of the times he lived through. Evan captured Hebrew calligraphy, too, not only in words but even in the borders. And his incorporation of doves is truly elegant. Every time I pore over his illustrations, I find something else to admire.

What do you hope young readers take away from THE PEOPLE’S PAINTER?

Evan: I hope that people take away a few things: I hope that young readers take away a desire to go out and see more of Ben Shahn’s work! I want him to be a household name again. But also, I hope that they see themselves in Ben’s journey to finding his voice as an artist, and take away the idea that each artist has to find their own reasons for creating, which is a beautiful freedom.

Cynthia: Above all, I hope young readers realize that art can be an eloquent and persuasive form of protest. There are many history lessons embedded in the book, which show that we are still dealing with the same issues he confronted—immigration, civil rights, voting rights, workers’ rights, income inequality, protests, political extremism, the role of government. Kids care about fairness, and they can illustrate it just as Ben Shahn did.

Thank you, Cynthia and Evan!

Since she doesn’t draw or paint, Cynthia Levinson tells true stories about brave people, like Ben Shahn, and the injustices they’ve faced through words. She loves doing research, which has allowed her not only to visit Shahn’s studio but also to walk with soldiers of the civil rights movement, fall off a tightwire, and read letters in a condemned building surrounded by police tape. Cynthia’s books for young readers have won many awards. She lives in Austin and Boston.

Evan Turk is an Ezra Jack Keats Book Award–winning illustrator, author, and animator. He is the author-illustrator of The Storyteller, You are Home: An Ode to the National Parks, and A Thousand Glass Flowers. He also illustrated Grandfather Gandhi and Muddy, a NYT Best Illustrated Children’s Book. Originally from Colorado, Evan now lives in the Hudson River Valley with his husband and two cats. He is a graduate of Parsons School of Design and continues his studies through Dalvero Academy.