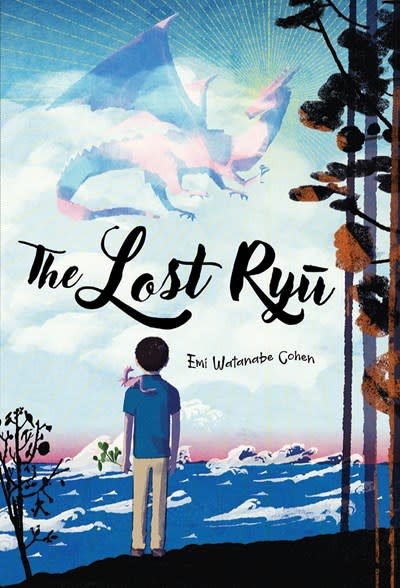

In Emi Watanabe Cohen’s debut fantasy middle grade novel THE LOST RYŪ (Levine Querido, 2022) set in 1965, Kohei Fujiwara embarks on a search for a big ryū, a type of dragon that disappeared after World War II. Although Kohei has his own beloved (but small) dragon named Yuharu, he hopes that finding a giant dragon from the past will please his ailing Grandfather, Ojisan. With help from his new neighbor Isolde, who is both Jewish and Japanese, Kohei finds friendship, understanding, and unexpected healing. The novel features fantasy elements and exciting world-building with heartfelt characters. I’m excited to learn more about the novel and hear what’s next for Emi.

Can you tell me a bit about the world-building for The Lost Ryū and what inspired the setting?

The Lost Ryū is set twenty years after the end of World War II. I’ve always been super interested in studying what happens after—after war, after catastrophe— and twenty years is a particularly interesting timeframe to explore. That’s when we see a whole generation of young adults coming of age having grown up with a trauma they didn’t experience personally. It’s a universal, yet oddly isolating facet of the human experience: We all move in the shadows of the things that came before us, but we can never truly see what’s casting those shadows. We rely on our parents and grandparents to provide that information, and when they can’t, things get complicated.

Most of the revision process for this book was done in quarantine, and as I was honing this story about kids confronting their parents’ history, I couldn’t help but think, gosh, this pandemic is going to define a generation. My generation is characterized by never knowing a world before 9/11 or Google; likewise, kids born today won’t remember a time before COVID-19 or Zoom. It’s a terrifying thing, having to hear tragic stories told in reverse, but it’s also a crucial part of being part of a community. Confronting the past is something we all have to do together.

In the novel, Kohei is on a quest to heal his grandfather by finding the magical dragon he recalls from his youth. What drew you to write about dragons as such significant beings?

I first had the idea for this book in the third grade. I loved reading books like Dragonology, which framed dragons as a species that could be studied and understood like any other. Many books specifically drew contrasts between East Asian and Western European dragons. It’s amazing, isn’t it? So many cultures have their own versions of dragons! There’s a distinct humanity to ryū, to wyverns, to lóng, to lindwurms.

But as a mixed kid, I found myself wondering why there weren’t any mixed dragons. What would interactions between Eastern and Western dragons look like? What would it be like if they could have families together? That idea stuck with me over the years, and it eventually evolved into The Lost Ryū.

Which characters came to you first – the humans the dragons?

This is probably a boring answer, but… both! My four main characters are Kohei (human) and Yuharu (ryū), and Isolde (human) and Cheshire (dragon). The first characters I developed were Kohei and Yuharu, and Isolde and Cheshire came soon after as both character foils and protagonists in their own right.

Fun fact: For a long time, Yuharu’s name was Koharu. It was much catchier to say out loud—Kohei and Koharu!—but far less readable.

Did you need to research a lot about the history of dragons?

The cool thing about dragons is that in many ways, we’ve all researched them. As I mentioned before, I loved reading fantasy books as a kid, so I had a basic understanding of modern dragon lore going in. Research-wise, my approach was primarily anthropological. The Lost Ryū is about creatures of myth, but also about how those myths can contribute to nationalist identity-building. While drafting, I read up a lot on the use of folk icons in propaganda, both in prewar Germany and in Japan. Dragons come up surprisingly often. They’re implicitly ancient and unknowable, yet also grounded in what was essentially early archaeology, and as such, they’re a potent source of nationalistic language. Japanese ryū in particular aren’t just physically powerful—like most dragons from the region, they also have ties to Chinese cultural and political hegemony. It’s really interesting stuff.

Kohei’s friend Isolde is of Japanese and Jewish heritage. Her dragon speaks Yiddish. Tell me a bit about this decision.

As I touched on earlier, part of the inspiration for this book came from my dragon-based identity angst, but part of it also came from the idea of generational trauma. This book is set in 1965, at a time when many Holocaust survivors were still either unwilling or unable to recount their experiences, and in terms of Isolde’s understanding of her family’s wartime experiences, it shows. She’s clearly pushed her elders for some details, but she can only push so far. All she knows is that something unspeakable happened.

Cheshire is fluent in Yiddish, and while he is a constant and powerful presence in Isolde’s life, he doesn’t talk much. World War II dealt a near-fatal blow to Yiddish communities, the Yiddish language, and in many ways, the Yiddish spirit. It makes the revitalization attempts we’ve seen recently all the more impactful.

What elements of the novel were inspired by Jewish folklore?

In this specific novel, not all that much is drawn directly from Jewish folklore. Jewish dragons are mostly Biblical, associated with Creation and Armageddon, and while I do want to write about them someday (particularly to explore their parallels with East Asian sea gods), they wouldn’t have fit into a book of this scope. My next book, titled Golemcrafters, will be more directly tied to Ashkenazi Jewish folk tradition, as the name implies!

Is there anything else you would like to share about your writing process?

One thing I’ve learned over the past year is that my writing process is always shifting. Speaking of Golemcrafters— this is the first time I’ve written a novel as anything other than a full-time student! Writing used to be the thing I got yelled at for doing in pre-algebra class, but now it’s my job. It’s definitely altered my workflow. But that’s the cool thing about creative work, isn’t it? It grows and evolves alongside you.

Thank you, Emi!

Emi Watanabe Cohen wrote her first novel when she was 12 years old — the most complete draft she can find clocks in at 234,780 words. That’s over 1,000 pages! Thankfully, her editing skills have improved since then. Her more recent work involves Jewish and/or Japanese folklore, complicated families, and a dash of improbable magic. She is a graduate of Brandeis University, where she studied Creative Writing. The Lost Ryū is her debut novel.